Take yourself back to the late months of 1999. It was a different time, wasn’t it? Cliff Richard was topping the charts (still), Jim Davidson was a Saturday night television star, and there was the very real fear amongst some that the world could end as we ticked into 2000. Like I say, different time.

Of course, Derby County was a different club at this point too. For a start, they were still in the Premier League and would be for another two and a half years. And it was in these final months of the 1990s that the club thought it was time to up the ante. Jim Smith’s side had started to stagnate and come October of ’99, it became painfully clear that any hopes of pushing on from their eighth placed finish the season before would be replaced by a battle at the other end.

Derby had lost stars aplenty by this point. Igor Stimac and Paulo Wanchope had departed for West Ham, with Francesco Baiano soon to be on his way. In attack, the work permit perils of Esteban Fuertes had thrown goalscoring options into the air and just eight points from the opening nine games left Jim Smith needing to act.

“How did it come about? It was quite a weird one actually. I got a phone call from our manager and he said, ‘You’re going to Derby tomorrow’.”

Lee Morris was a coup. Battling Arsenal for the Sheffield United graduate’s signature, it was a club record fee of £3 million that would lead the then 19-year-old to Raynesway.

“I’d been at Sheffield United for a while and didn’t really want to leave. But they had serious financial issues there. It had been ongoing but I’d broken my foot in the summer so it wasn’t until October the deal materialised.”

Morris’ capture should have been huge. He’d been tipped for England and the £3 million spent on him was a significant outlay for the club. In fact, so significant was it that it remained the record fee paid by Derby until Robert Earnshaw almost eight years later.

But it was right here, at the very first step of his Derby County career, that Morris’ problems started. Having missed the first months of the campaign in the then First Division, a cash-strapped United fast-tracked the forward into their side, likely done to prove his fitness to his would be employers. And it worked – at least for United.

“I basically trained (at Sheffield United) on the Thursday, thought I was six weeks away from being fit. But I played on the Saturday away at Crewe, which I thought was strange having only trained one day. And then on the Sunday, I got a phone call saying I was going down to train with Derby. I trained all week with Derby and started at the weekend against Tottenham. It wasn’t a huge surprise when I broke my foot a couple of weeks later.”

“I was six weeks away from being fit… it wasn’t a huge surprise when I broke my foot.”

To those readers who may not have enjoyed Derby County in their maiden Premier League run, you might be coming into this with an open mind and without too much of a knowledge of Morris. So, to put this into perspective, he was the George Thorne of his time – except he was even more unlucky with injuries. Morris would make 92 appearances for Derby in four and a bit years, plagued by broken bones, strains and incredibly bad luck. And it all began from day one.

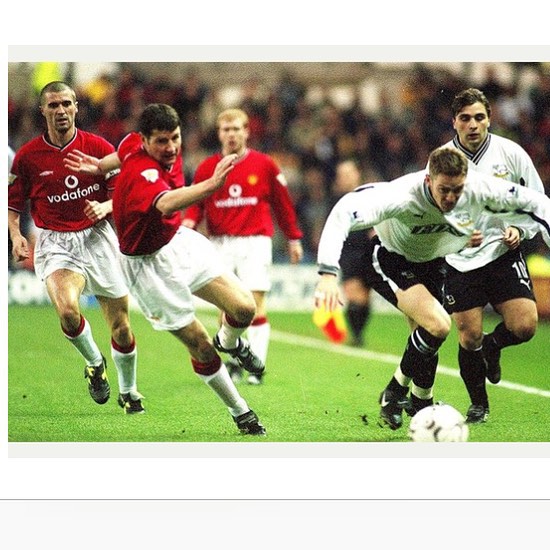

A barely 50% fit Morris would play an hour in a 1-0 defeat to Tottenham. And then he’d play in back-to-back games against Newcastle and Chelsea. But he wouldn’t appear again until August 2000. And during those off months, he had the slow realisation that life under Jim Smith was maybe not what he expected.

“This is all in hindsight but I wasn’t Jim’s type of lad and he wasn’t my kind of guy” admits Morris. “I had come through a youth system at United and was one of the best players, so was always treated as a young guy coming through and people were telling me how good I was. Then all of a sudden, coming to Jim was completely different. He was as old school as you could be and every solution was solved by shouting. If it didn’t work, he’d just shout louder. We were on a different page.”

And it should come as little wonder – considering the two were on different pages – that Morris would never find his best form under the Yorkshireman, then adored by Rams fans. “I was still trying to learn the game and needed help, he thought I should be the final product. Looking back, I was young and I feel like I could have been more successful if I was handled better. But it was a learning curve and it forced me to grow up quick.”

“In hindsight, I wasn’t Jim’s type of lad and he wasn’t my kind of guy”

That learning curve was twofold. Yes, Morris would have to learn what life would be like under Smith. But he’d also learn what life was like with top flight footballers, and international stars to boot. “We had Stefano Eranio, (who) was so good. If it was cold outside at training, he’d just say ‘not today’, go and have a cup of tea and do what he liked! Nobody would ever question that, it was just different how a young guy was treated. But how I would be treated and Seth Johnson was treated would be different. If you shout at Seth, he’d roll his sleeves up. But I needed telling how good I was.”

And with confidence being a major part of Morris’ game, it would be little surprise if it began to sap, the longer he was forced to watch on from the stands. By the time of his recovery in the season of 2000/01, he would rejoin training sessions with a side desperate for goals and staring the First Division in the face, as Smith’s initial Premiership fire had been extinguished.

But despite being fit, young and itching for an opportunity, it would be at the Baseball Ground he’d be donning a Derby shirt, as part of the reserve set up. “I just felt frustration. I missed the whole first season, came back the next season and felt in a position to start playing games, but always felt I was trying to get it and never had total confidence. A goal would have solved those problems.

“What’s really hard is when you’re on the outside and you don’t feel you’ve got the belief of the manager or the staff, so you can just come in. I remember scoring a hat-trick in a reserve game at the BBG against Arsenal under Colin Todd. I wasn’t even in the squad for the Saturday. That was a time when Malcolm (Christie) couldn’t buy a goal in the first team, I just couldn’t understand. I felt I’d never get given a go, so what can you do? That’s hard and it’s where the confidence struggles.”

Come the end of Morris’ second campaign, he’d begun to force his way back into contention, starting in the 1-0 victory at Old Trafford that secured a top flight spot for another year. But yet, here was Derby’s record breaking man, 17 months into his time at the club and still without a goal. Injuries, confidence and lack of opportunities had stripped Morris of two years of football.

“I remember scoring a hat-trick at the BBG in a reserve game. I wasn’t even in the squad for Saturday.”

And as if that wasn’t bad enough for his development, he was soon to be stripped of his shirt number, too. The eleven adorned onto his back would instantly be handed over to the incoming Fabrizio Ravanelli. Morris’ time at Pride Park under Jim Smith was getting worse by the month.

So, when Smith was replaced as manager by Colin Todd early into 2001/02, while fans were sorrowful to see the Bald Eagle depart, Morris saw it as a new opportunity to prove himself. Yet still, with a new manager, he wouldn’t be given first team football. And then it all became clear to him. This wasn’t football related at all – Derby were skint.

“Nobody told me that if I made one more appearance, we’d have to pay Sheff United another £500k. I couldn’t go out on loan, I was stumped, not getting picked and I didn’t know why.” Such was the financial hardship of the club, Derby’s situation was approaching such a dire situation that they left Morris on the sidelines to save half a million.

Smith and Todd would adhere to the situation, but John Gregory wouldn’t. And that’s why it came as little surprise that finally, more than two years after putting pen to paper, Morris was able to find the net in Gregory’s first match, a 1-0 win over Tottenham. “I felt if John had come along a couple of months earlier, we might have got out of it. John had belief in me. I’d been out in the wilderness but it was just little things that showed he was a top bloke. With John, someone believed in me and I started scoring. But unfortunately, it came when we were falling out of the Premier League.”

The final months of that campaign were the ones Morris staked his claim and showed what could have been. The winner against Spurs, three more goals including one in the 3-0 victory at Filbert Street. Had Derby bit the bullet and stumped up £500k more, the end result of the season could have been very different. But ultimately, it was too late and with Gregory’s initial success up by matchday 31, Derby dropped back into the Football League.

And within it, Morris would struggle again. Not for goals, for fitness. The maiden Division One season would see him strike nine times, the 2003/04 finished for him by January. That first campaign was marred by more financial mire, not helped by the wage packet of Ravanelli. At that stage, it was tough. Your flagship player just goes missing. Your manager asks you to run through brick walls and then somebody else is just not turning up at all. So it was a weird thing. He had an injury that apparently, he could only get treated in Italy, but our physios couldn’t find any injury whatsoever. It was just strange.”

“The manager asks you to run through brick walls and then somebody else is just not turning up at all.”

And with George Burley then forced to cut costs further, Morris’ record breaking time at Pride Park would come to a close.

But Morris looks back fondly on his Derby days. “What was funny was Derby is a one club city so it is a fantastic place to be when things are going well. Even now we’re always on the brink of the play offs and it always feels like PP is full and everybody wants the club to succeed. At other clubs, that might not be the case if there’s two clubs in the city or more. It was a transition time though. And it was hard.”

Still, even three and a half years after departing, he gave Rams fans a feeling of what could have been, a goalscorer on that glorious night Yeovil put five past Nottingham Forest in the League One play-off. And it’s a night he’s received plenty of plaudits for from those who years earlier were simply dying to see the best of him in black and white. “The Forest semi was very special! With Russell Slade, we were favourites to go down so to beat Forest was special. On their scoreboard they were selling bus tickets to Wembley. And for me personally, coming back from a cruciate and playing 120 minutes was special. I got a load of messages from Derby people congratulating me!”

But although Morris recalls his Derby career ‘never really hit the heights I hoped’, there’s a whole other side to the now 40-year-old that many aren’t aware of. Because though 17 years have passed since his playing days at Pride Park came to an end, he’s had a huge say in how the future of the club looks through his work behind the scenes up until 2016.

“I was in the academy for nearly four years” he reminisces. “It’s strange because I feel like I had such big learning experiences at Derby as a player, and then again as someone learning how to coach. Derby made a huge impact on my life.”

Moor Farm is no Raynesway, and rightly so. The now derelict land that once homed the RamArena is a part of Derby’s past, with Moor Farm the undisputed home of their future. And for a Morris who was looking for a step into coaching at the back end of his career, there was no better place to learn his second trade. “The academy is a phenomenal place. Darren Wassall, Pat Lyons, all of that crew are brilliant people. I was really lucky to spend time there developing as a coach. And especially to be around so many talented players.

“The coaching side is as much of a sense of pride, it’s a really special academy, and it shows in just how many players they are producing to many different levels.” And of those players coming through now, they’ve all been through Morris’ coaching at various age groups. Louis Sibley, Max Bird, Jason Knight. All progressed under Morris’ tutelage, with his impact being felt stronger than ever during the transition from old guard to young guns.

Morris isn’t at Moor Farm now, though. No, he’s swapped quiet Derbyshire for a stint in South Carolina back in 2016, and the plan is to stay there long-term. “I’m in the deep South. I was an apprentice with a lad at Sheffield United and he came here to universiy just up the road. But he worked for a club here, started coaching and became CEO. He reached out and asked if I fancy it. So yeah, it’s about 90 degrees right now. Not a bad place to be living right now! But I’m here because of Derby!”

Pride: The Inside Story of Derby County is now available from the DCFC Megastore and to pre-order from Amazon and Waterstones. From Stefano Eranio and Colin Todd through to Harry Wilson and Gary Rowett, it’s the story of Derby since 1995 by those who know it better than anybody.