“Did you come to Milan in December? You didn’t? Oh well we must go to a game, organise the trip before the end of the season and we’ll watch an AC game. We stay in touch!”

It’s quite rare that when you ring up a footballer or retired footballer for an interview, they pay an interest to the human on the other end of the line. For the interview stages of Pride, I would nervously wait before entering a phone number, walking through a Costa door or making my way into a Premier League training facility. I’d be well aware that interviews were just a part of their daily routines, but there’s still something daunting about sitting down with people you have only ever idolised from afar.

On the night I was to hit the call button, this situation was no different. Scampering away early from the leaving drinks of my then manager, I explained to those around the table that I would probably be back in around 15 minutes or so. I anticipated some basic answers to some basic questions, if I got any responses at all. Late 2019 and early 2020 saw me swallow my pride on a frightening amount of phone calls that would be ignored.

And so, I dialled the number given to me by a member of the AC Milan academy’s communications team. And I waited. And then I waited a little longer. I hovered over my trusty blue notepad, ready to jot down another X on the call list.

“Ryan! Hello!” came the response.

The conversation began with an apology. “Sorry for my English!” Eranio chuckled. “I hope that you understand everything I say, this is just English practice!” His English was perfect. Of course it was, this was Stefano Eranio. To Derby fans, everything he ever did when in possession of a football was perfect.

There are few individuals who can leave such a lasting impression on a football club as the one he made. His four years at Pride Park brought no trophies, no European qualification and even culminated in the imminent threat of relegation. And yet, he is idolised, worshipped. If Igor Stimac was the King, Eranio took his crown upon abdication. “To this day, I get his name on the back of every home shirt” supporter Elgan Thomas told me. “Last year, a young fan asked me ‘what does Eranio mean?’ as it’s on the back of my shirt. I replied, ‘It’s the name of the greatest player to ever play at Pride Park’.”

Thomas isn’t alone. Eranio’s impact is so heavily felt that he was voted into the Derby County Greatest XI that marked the 125th anniversary of the club. Nobody’s footballing ability has ever left such an impression on Derby County supporters. Not Wanchope, not Ravanelli (apart from financially), not Abdoul Camara. Not even Wayne Rooney will be able to match the imprint Eranio left on Derby hearts around the turn of the millennium.

That’s because he was, at the time, one of the best footballers on the planet. At a period where Jim Smith was transforming sleepy Derby into a haven of world footballing talent, there was no more significant capture for the Rams place on the world stage than Eranio. “We have signed one of the best wing-backs in Europe and it’s very exciting for the fans and for me.” Those final words, ‘for me’, are most telling. When a signing is enough to bring out the gushing fan in Jim Smith, the grumpiest (in a very, very lovable way) manager of the mid-late 1990s, you know the individual involved is special.

Signing for Derby despite interest from major sides across Europe, Eranio would enter the East Midlands for the first time in his life. Without a word of English in the bank, his first weeks would be make or break. “From the first day, the children went to an English school and learnt it much better than me” he laughs. “Now, if we speak about football, I understand it much better for me, but English can be difficult. It takes me a while to reach the words. Now, this is practice for me because if you don’t, you lose the words!”

Practice makes perfect. And for Derby, that second ‘p’ was what Eranio was. He would arrive on Raynesway boasting 20 caps for Italy, a national side that contained Roberto Baggio, Gianluca Vialli and Paolo Maldini. That’s why every stop was pulled out for him when he touched down in England. “Me and my family, we were all together from the first day. Inside two weeks they gave me the apartment and we bought a place near Mickleover. Our first two weeks were in the Mickleover Hotel and in two weeks they then gave us the apartment. The vice chairman, Keith Loring, he gave to me the possibility to buy the house. And so I bought it and all of my family moved with me.” It would be the home of the Eranio’s for four years

“Jim tried to bring me in to play golf, but I was used to a sport that actually had movement. It was no good for me!”

Though they had each other, the Eranio’s knew that Italian families in Mickleover were rare. And so, as they settled into their new life and struggled their way into English lessons (the Duolingo owl was at this point just a pipedream), it was his new teammates who helped them make the adjustment. “We tried to all stay together away from football and so for us, it was incredible.

“Jim tried to bring me in a lot of the time to play golf. But I was used to playing with a ball that actually had movement, it was too slow and not a good sport for me! With the guys who spoke similar languages like Spanish and Italian, it’s not exactly the same, but there was Wanchope, Carbonari, so we spent time together. But with Baiano, he was my neighbour and all the time we were so close. My daughters with his daughters, the relationship was great and we spent so much time with each other.”

It showed. Francesco Baiano only joined Derby because Eranio told Smith to make it happen, Smith looking to fill the void that Roberto Baggio was due to move into. When Baiano missed the penalty that would have made him the official first scorer at Pride Park, he turned to his Italian compatriot to fire the retake home. That afternoon against Barnsley was a second chance for Eranio, although he’d hardly fared badly in the original abandonment against Wimbledon, scoring once.

Leaving Serie A for the Premier League was a bold step. Yet to become the financial beast that it has morphed into today, England’s top division was still playing catch up when compared to Italy and Spain. So much so that before making the move, Eranio had no idea how the league would suit his style of play. “I didn’t watch the team before and the football, I think I’d seen a few games but it wasn’t enough to see what it was like or what the players were like.

“We tried to bring some Italian styles of football when we came in. Now English football has changed the style because Liverpool, Man City and many other teams play great football, but in that period, English football was a little bit different. You can take Manchester United away, Arsenal too because they had great players, players like Emmanuel Petit and Dennis Bergkamp. But there were teams who grew to play great football and that included Derby County. Because in the first six months, nobody knew Derby but we played one of the best styles of football in England. I had many great days with Derby, especially in the first season, not just for me but the whole team. I think that everybody was important for the team because the manager tried to build a great team without spending so much money.”

Eranio would move seamlessly into the top flight of English football. This fresh Derby, heading into 97/98 off the back of a strong first campaign, was an anomaly for opposition sides. Whether it be the ingenuity of Eranio, the calmness of Stimac or the sheer terror brought upon defences by the human wrecking ball Wanchope, the goal quickly became a European spot.

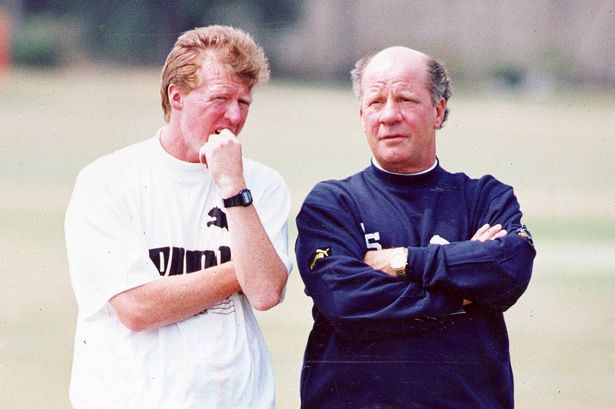

Spearheaded by Smith and masterminded by Steve McClaren, the pair were taking Derby further than anybody ever anticipated. “They were two great people, Jim and Steve” Eranio enthuses. “For me, Jim was like a father. He was a great man, very direct and if he said something to you it would always be straight into your eyes. For me it was incredible to work with them.

“It was easy to stay in Derby because I was a very professional player, I helped him when he asked for something within the tactical system on the pitch. He would always ask for my opinions on the pitch and help me to help the younger players grow in the right way so it was a great relationship between us.

“Also, with Steve. He used to stay on the pitch at the training centre, because it was he who tried to do the work on the pitch. The manager would sometimes be outside with a whistle and stop the game to say something to us, but Steve was a great part of the team. On the pitch, the maximum work was what he did.” McClaren himself ran out of superlatives to describe Eranio, most of which can be found in Pride.

“They were just a great, great side” remembers journalist Nick Britten. “They were the best side Derby have had since the ‘70s. There was a real peak and a generation of Derby fans now, they were the first team that they really engaged with and there hasn’t been a better one since. Arsenal, Liverpool, they came to Pride Park and were sent packing. Not only sent packing but done in style and it was wonderful to watch.”

Eranio was a major part of that. But to him, it was just part of his work, part of his experiences. He was no stranger to facing the biggest sides in world football and winning, his years at the San Siro ensuring that. Departing Genoa for Milan in 1992, his five years in the Italian capital warranted every possible trophy he could win. He had won more titles in that time than his new club had in their entire history.

There were three league triumphs in five seasons, the Supercoppa Italiana as many times. Then there was the Champions League triumph in 1994, sandwiched between two other final appearances. Add in a European Super Cup for good measure. And he was even an AC player of the year, at a time when they boasted Frank Rijkaard, Marco van Basten and Franco Baresi.

So, to have gone from those heights, you’d perhaps expect an aura about the man. There’s little doubting he was too big for Derby. Given his accolades, he was too big for most clubs in European football. It’s why you could have forgiven him to do things differently, treat people differently.

He was even an AC Milan player of the year, at a time when they boasted Frank Rijkaard, Marco van Basten and Franco Baresi.

At the top of this piece, I spoke of how Eranio paid an interest in me: a nobody. To him, I’m just a person at the end of a phone who pestered him with WhatsApp messages while hoping to arrange a chat for a book he would probably never, ever read, or almost certainly never see in a shop. He could quite easily have just not replied or done the bare minimum. But his interest was genuine.

The man at the end of the phone that night cared. About who he was talking to, what we were talking about, his history at a club he had so many happy years. He always has cared. About his friends, his teammates, his family. In the run up to our conversation, he proudly told of how he’d recently became a grandfather and he was struggling to find the hours to sleep, such was his intention of being involved and helping his family. From 1997-2001, that family bubble he encircled himself with consisted of his teammates.

“You learn from people like Eranio” Chris Riggott recalls. “He is a fantastic man in how he conducts himself with everybody. He had this amazing career but was the most humble of men. These are important lessons for a young lad when you’re watching these guys and how they interact and how they handle themselves.”

Riggott wouldn’t be alone. Youl Mawene remembered him to be, “a magician, he’s just someone you can’t not learn from.” Deon Burton would say, “He still brought a lot to the table and showed us the way it should be done. Coming from his background, you can’t not listen and learn from him.”

“He had this amazing career but was the most humble of men.”

Chris Riggott

It’s not just those he shared a pitch with who would get to experience Eranio. Long-serving kitman Jon Davidson was there for his arrival and has been there for his fleeting visits in recent years. “I see Poomy and Eranio a few times, Stimac too. They always, always come straight up to me when they see me. People upstairs now don’t realise sometimes and they look at me like ‘how do you know him?’. Well, I’ve been here for a long time!”

And for Elgan Thomas, the then-boy-now-man who worshipped the very ground Eranio walked on, he had first hand experience of engaging with his idol. Derby’s mascot for a 2000 visit to Goodison Park, he’d find himself paired with the Italian, who was by then sporting the armband. “The Bald Eagle ushered me into the changing room where he introduced me to Stefano, and I was in awe as he was my hero. He took me round to meet all the players and made me feel incredibly welcome. I remember walking out on to the pitch, doing the pre game photo and then having a brief kick about with the team, where, despite me being absolutely awful, I passed the ball to him, and he sang my praises. It was an incredible moment.”

When it comes to supporters, he’s not alone. Earlier this year, the official Derby twitter account tweeted a clip of Eranio’s sumptuous goal against Leicester. @PablaTech responded with “I remember seeing him in the fish & chips shop across from Eagle Centre. Lovely chap, he was nice to everyone.” Over on Facebook, Richard Allison responded with “Managed to get his autograph. He asked me if I liked Italian food.”

Eranio would spend four joyous years in England, before the culmination of his contract in the summer of 2001. After a standing ovation in his final outing at home to Ipswich, he flew back home. But even then, such was the hold that the club, the supporters and mainly Jim Smith had on him, he opted to return for one more year. “When I left in 2001, after three months I came back to Derby! I came back just for Jim Smith because he asked me if it was possible because he was looking for a player with my characteristics and he asked ‘Stefano, please come!’. I said to him ‘please give me one month’ because I hadn’t touched a football for three months.

“I should have retired but when he called, I came back, asked for a month and one week before starting again, Jim got sacked. For that reason, I left. The second time I came here my family stayed in Milan so I was on my own. I asked that he must let me have the possibility to visit my family but when he was sacked, I just had to finish.”

Come February 2020, Derby still meant as much to Eranio as it did two decades earlier. Though he is far gone from the city, the city never truly left him. “Who is the manager now, the Holland guy?” he asked enthusiastically. “And Rooney is there too now! He came back from America to play, didn’t he? But how many players are in the team from the youth now? I think there are a few, aren’t there? In what position do they play? Who have you spoken to? Chris Riggott! Oh Steve McClaren! Oh, that was such a great time! I left some of my heart in Derby.”

His interest in the youth, the recollection when presented with names of his once teammates and lifetime friends. Derby is still a period of time that means so much to the man. It’s why he returned temporarily when McClaren did in 2013, willing to dedicate almost a week to his former club and his former coach. And it’s why he came back to Pride Park as part of those 125th anniversary celebrations. And in 2017.

As we approached the final seconds of our conversation, Eranio signed off with ‘ciao’. Nobody ever says ciao in Derby, but then nobody ever did what Eranio did in a Derby shirt.